7 Helping students become effective online learners

Most students don’t have experience learning in an online format. They may be comfortable but not necessarily proficient online. Students haven’t chosen to work in this remote format and most would have chosen to be in a face-to-face class. You can ask them about their experience using a Google Drive form like this, which can be adapted to your own context. As such, they could use help knowing how to work effectively online.

Most students don’t have experience learning in an online format. They may be comfortable but not necessarily proficient online. Students haven’t chosen to work in this remote format and most would have chosen to be in a face-to-face class. You can ask them about their experience using a Google Drive form like this, which can be adapted to your own context. As such, they could use help knowing how to work effectively online.

Supporting Students as Self-Directed Learners

TRU’s Centre for Excellence in Learning & Teaching’s (CELT) suggests the following strategies for supporting students and fostering their intrinsic motivation to learn during the shift to remote classrooms which will require more than ever that students take responsibility for their own learning.

1. Give students choice whenever possible—but limit the options to provide guidance and avoid overwhelming them. While unlimited choice can be overwhelming, giving students some autonomy in their learning can foster their motivation to learn. Can they choose their project or paper topics? Can they choose some of their readings or learning activities? Can they choose from a list of options about what format an assignment will take (paper, presentation, video, podcast, etc.), as long as they are demonstrating achievement of course learning outcomes?

2. Make course material relevant to students’ lives. Demonstrating the relevance of your course content to their lives will go a long way in encouraging them to engage with your course. Can you relate your course concepts to something happening in the world? Can you let students know why they may find this information or these skills useful in the future?

3. Provide opportunities for students to practice using skills and knowledge in a safe, low-stakes way. Are there opportunities for you to assess students formatively, in a low-stakes way designed to offer helpful feedback before a graded task? Can students write practice quizzes, complete drafts of an assignment or lab report, or get feedback in some other way? If you have clear assignment criteria, you might even be able to allow students to self-assess, or to peer assess, using your criteria to reduce marking work/time for you.

4. Ask students to articulate their learning when possible, including their processes for undertaking tasks and applying skills and knowledge. Providing students with a few prompts to get them thinking about their learning and how they learn can help them learn better and more deeply. For example, asking a student to articulate their writing process, problem- solving process, or approach to undertaking a task encourages them to consider what works and what doesn’t. Asking a student to identify their three main takeaways from a video or reading or lab report will help them to see the value of the exercise, and it will also highlight—for them and for you—where their learning has and hasn’t happened.

5. Encourage student input into the course whenever appropriate. Student learn best when they feel invested in a course, so find ways to allow them input and feedback. For example, could the students offer feedback about your grading rubric (or other marking tool)? Could you negotiate categories or criteria weighting with them? Can you ask them to self-assess with the same tool? Even if you can’t change the rubric, having an open discussion with your class about how marks are determined can go a long way to fostering students’ investment in your course—and in their own learning.

Resources

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., Norman, M. K., & Mayer, R. E. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching (1 edition). Jossey-Bass.

Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Harvard University Press.

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Press.

Bowen, J. A. (2012). Teaching naked: How moving technology out of your college classroom will improve student learning (1 edition). Jossey-Bass.

Doyle, T., & Zakrajsek, T. (2011). Learner-centered teaching: Putting the research on learning into practice. Stylus Publishing.

Lang, J. M. (2013). Cheating lessons: Learning from academic dishonesty. Harvard University Press.

Lang, J.M. (2016). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning. Jossey-Bass.

Nilson, L.B. (2013). Creating self-regulated learners: Strategies to strengthen students’ self- awareness and learning skills. Stylus Publishing.

Pink, D. H. (2011). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice (2 edition). Jossey- Bass.

Supporting Students in Remote Group Work

CELT notes that “Group work is challenging to manage at the best of times; it’s even more challenging in a time of social distancing. These tips should help you support students as they try to navigate the challenges of working in groups remotely.” They suggest the following strategies for support:

1. Remind students NOT to meet in person during the covid-19 crisis. Yes, there projects are important, but not as important as their well- being. Plus there are many, many options for them to discuss virtually. If you haven’t already done so, set up group discussion forums for all groups in Moodle. The Moodle Support Team can help you with this if you don’t know how to do this.

2. Whenever possible, ask students to create group agreements, contracts, or charters, so it’s clear who is responsible for what— complete with agreement about what happens if group members don’t agree or don’t complete their work.

It’s not likely students will agree all the time in the best of times, so we can’t expect all projects to run smoothly now with the added stressors of COVID-19. Provide students with a template to create a set of agreements to help them complete their work smoothly, including provisions for what they can do if they don’t have good internet access— and what will happen if someone from the group becomes ill. Need help with this? Contact the CELT Team at celt@tru.ca. Also, Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberley Center has some helpful templates here.

3. Encourage students to come up with a team name. This may sound silly, but belonging to a team with a name helps students feel they belong. Team names help groups form identities, and this helps create community. Community is especially important when groups cannot meet in person.

4. Remind students that they can accomplish more as part of a group than any one student can accomplish individually. This helps them understand the rationale of group work in a time that isn’t conducive to group meetings. Allow them to see that the group’s success depends on everyone contributing, and that their success is linked to the success of others.

5. Provide examples of how students can break projects up to work independently. Can you help students divide tasks or content? Can projects be divided in ways that allow students to work to their strengths?

6. Provide both individual and group grades, if possible. Students need to feel like they have some autonomy over their own grades. Ask students to self-assess and describe their own contribution to the group project. Students also need to feel accountable to the group, so ask them to peer-assess and describe their own contribution to the group project. We in CELT can help you create rubrics for this; e-mail us at celt@tru.ca. Also, Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberly Center has some helpful templates here.

7. Ask students to reflect on their learning from the group project. Provide them with prompts, such as “What was the most important thing you learned about [TOPIC] from working on this project?,” and “What are you most proud of with this project?,” and “If you could do it all over again, what would you do differently?” These kinds of prompts can help students feel positively about their group experience, and reflection fosters deeper learning from that experience.

Resources

Barkley, E. F., et al. (2014). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. (2nd edition). Jossey-Bass.

Burtis, J., & Turman, P. (2006). Group communication pitfalls: Overcoming barriers to an effective group experience. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Eberley Center. (2020). Sample group project tools. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/instructionalstrategies/groupprojects/tools/index.html.

Forrest, K., & Miller, R. (2003). Not another group project: Why good teachers should care about bad group experiences. Teaching of Psychology, 30, 244-246.

Gueldenzoph Snyder, L. (2009). Teaching teams about teamwork: preparation, practice, and performance review. Business Communication Quarterly, 72, 74-79.

Hammar Chiriac, E. (2014). Group work as an incentive for learning: Students’ experiences of group work. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1-10.

Hansen, R.S. (2006). Benefits and problems with student teams: Suggestions for improving team projects. Journal of Education for Business, September/October, 11-19.

Kilgo, C., Ezell Sheets, J., & Pascarella, E. (2015). The link between high-impact practices and student learning: Some longitudinal evidence. Higher Education, 69, 509-525.

Vittrup, B. (2015). How to improve group work: Perspectives from students. Faculty Focus. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/how-to-improve-group-work-perspectives-from- students/

Weimer, M. (2014). 10 recommendations for improving group work. Faculty Focus. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/10-recommendations-improving-group-work/

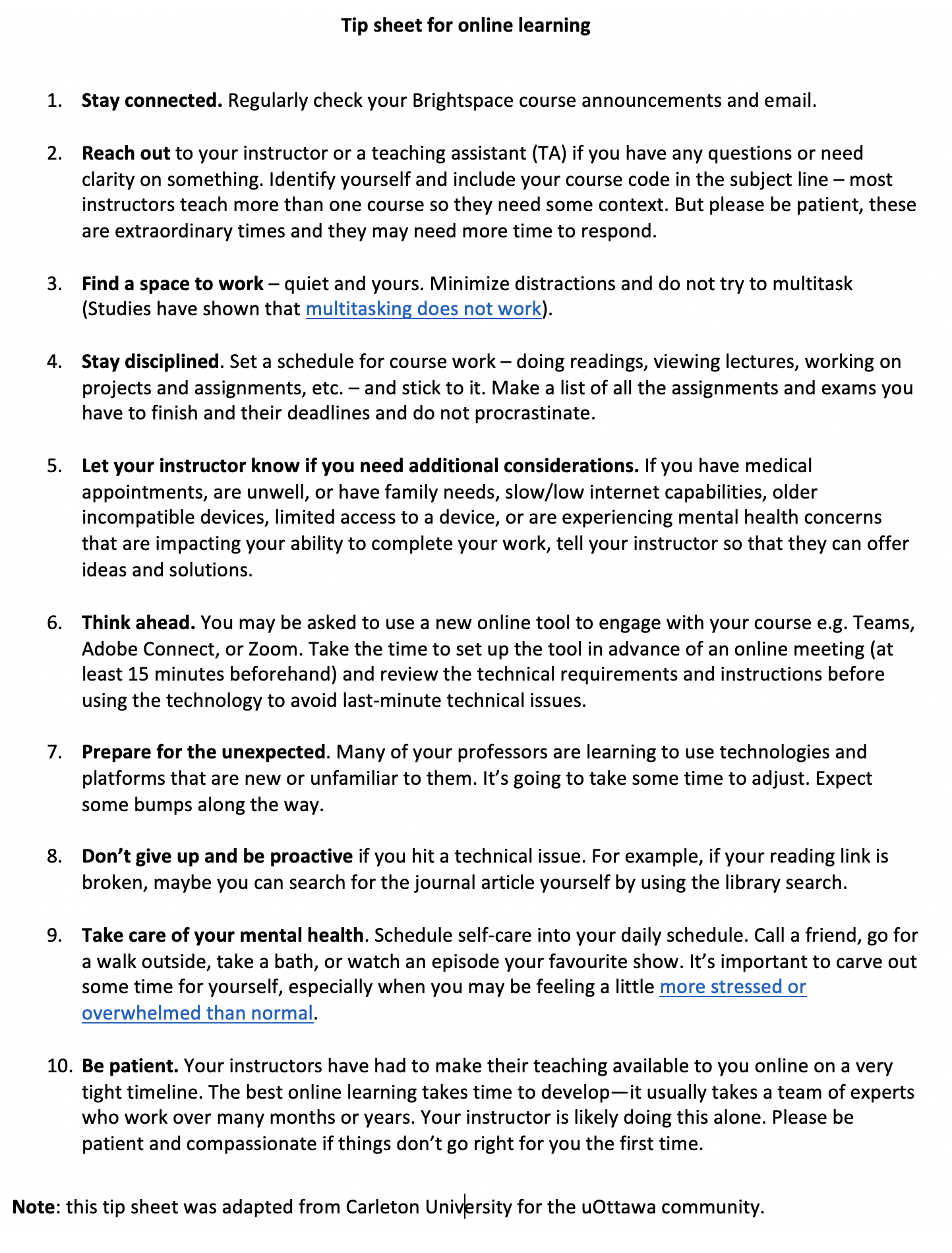

Provide a tip sheet

This tip sheet gives a quick, clean starting point; it was adapted from Carleton University. The adaptable version is available in the chapter: “Quick start overview and resource documents“.

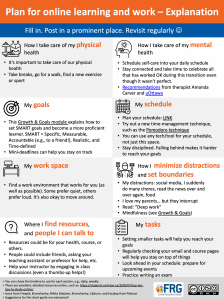

Provide a worksheet

This adaptable worksheet can be used to set goals and make a plan, and includes explanations and examples. The file can be found in “Quick start overview and resource documents“.

Encourage developing learning skills

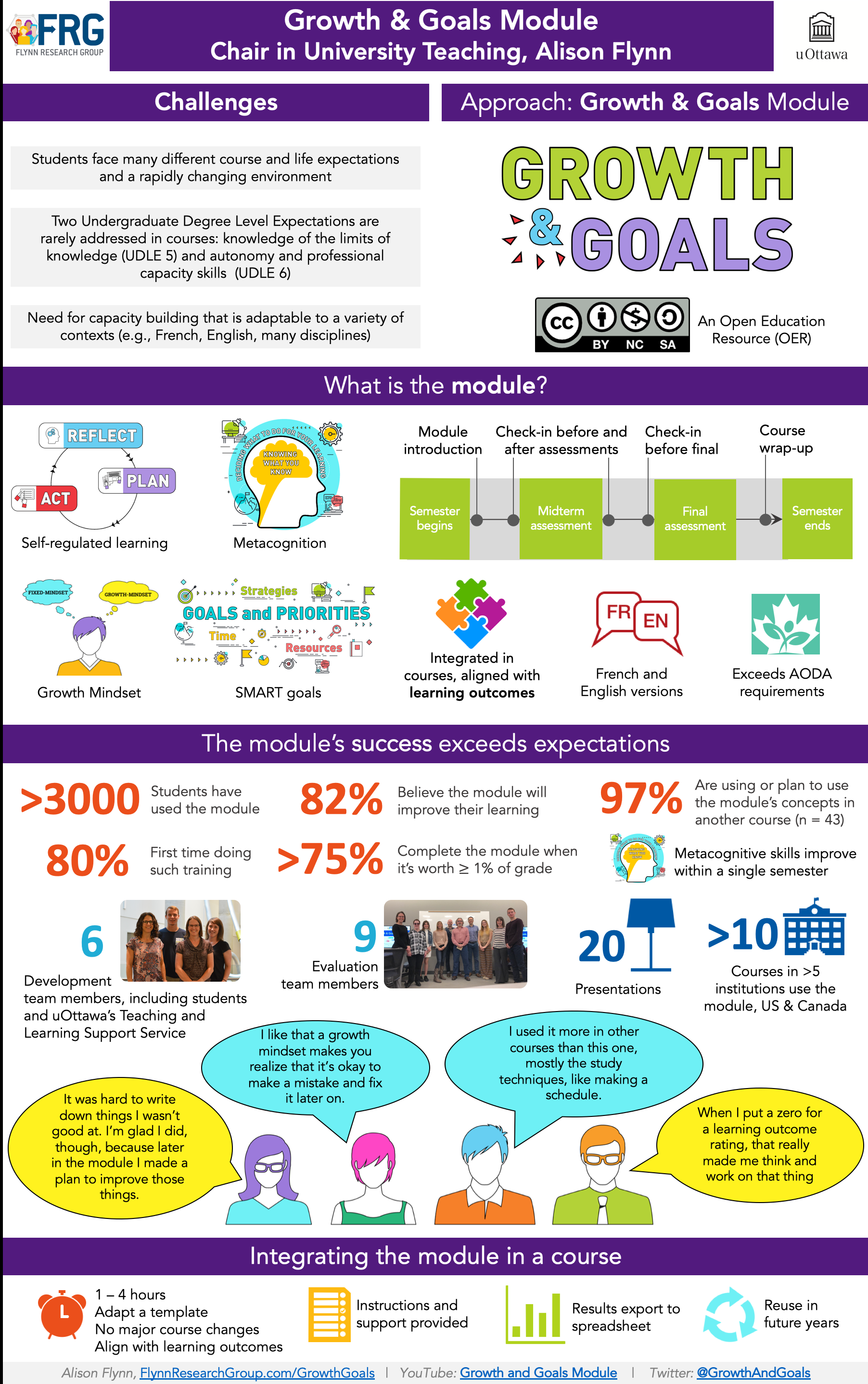

The Growth & Goals module was developed to help students become more efficient learners.

Two version are available in English and French:

- a course-integrated version, meant to be linked with the course’s intended learning outcomes, ideal study strategies, and support options

- a course-independent version, which can be used by anyone in any area (e.g., academic, athletic, artistic)

The infographic below gives a brief overview of the module.

To go deeper

Develop (and share?) your own methods of supporting students with the education community.

Up next

The next chapter provides step-by-step instructions for many aspects of Moodle.

Google Drive Forms can collect information (questionnaire) and even be used for quizzes. To adapt forms:

- Sign-up for/Log in to a Google account

- Click on the link to the forms you wish to copy

- Right click on the form and select "Make a copy"

- Now you can adapt the form to your own context.