3 Design for the online environment

Introduction

Designing for the online environment takes a different approach to what you might do in the face-to-face classroom. Decisions around assessments, activities and weekly tasks need to be made in advance, as it is much more challenging to change on the fly. Though ideal for any environment, explicitly outlining outcomes, expectations, timelines, assessment strategies are requirements for digital spaces, where time and space are experienced differently. In this chapter we will outline some suggested planning tools, and ways to think about time for both you and and your students as you then design your online space by selecting different strategies and tools to support them.

This section was inspired by a fantastic resource put together by Humber college – here is the link if you want to explore their 10-Step Design Process.

We will be breaking this chapter into 2 parts:

- Planning

- Design

Planning

There are a variety of steps in the planning phase, but first you need to gather the materials you will need. Starting with your course outline or syllabus, and as highlighted in the previous chapter, first evaluating your learning outcomes for the course. We often follow a backwards design approach for online where you start with outcomes, determine the assessments, and then build in the types of activities that will support your learners in being able to demonstrate how they have met those outcomes (through various formative and summative assessments). So in your first phase you will gather all the resources you typically use and then organize them into an overall planning document. The next three chapters provide more detail on how to create and curate resources and choose and build assessments, but the first step in planning is to bring these ideas together.

In Open Learning at TRU, as part of the online course development process we build what we term a blueprint. This blueprint contains our outcomes, assessments, assessment weightings, information about the students and target audience, and then a table where we outline the structure (by weeks, units, topics or modules) that links outcomes, activities and assessments.

Here are links to a few blueprint templates:

Blueprint-Template-Table Blueprint Template 1

Links to the Humber templates:

Online Course Design Tool – Fillable Form V5 (PDF)

Online Course Design Tool – ODF (Word)

Course Build Design Tool EXAMPLE – Fillable Form V1

Here are links to some exemplar blueprints for various online courses:

PSYC-3151_Blueprint_2Nov2012_JK BIOL-4141-Blueprint-_draft_shf_05Oct09_1

BIOL-4141-Blueprint-_draft_shf_05Oct09_1

Design

As you are putting your blueprint together you will be making decisions about activities, technologies and assessments. A few key areas that we will explore further in the sections below include:

- Time and timing

- Schedule and organization (student time)

- Real-time vs anytime (synchronicity)

- Developing and establishing community

- Building Community

- Maintaining connections

- Aligning Assessment and Activities

Time and Timing

Schedule and Organization

Ideally, each course decision will be aligned with:

- The intended learning outcomes

- Your intentions for the course, such as the learning experience you hope students will have

- Abilities: both yours and the students’

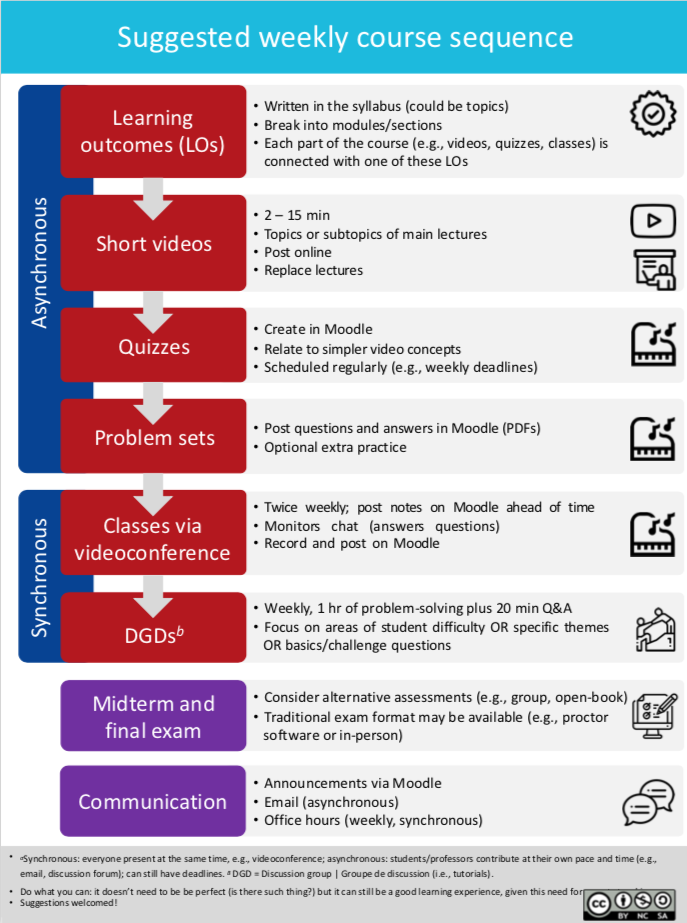

The following graphic depicts how the various elements can play out in a course. Please feel free to adapt and share with students. PDF version Quick start overview_TRU.

There are a variety of ways to organize your course, but chunking your course into weeks is often an easy structure for students to follow. They determine what activities and assignments are due, and when they can work independently vs. tasks that they will work with others. Flexibility in timing is something to consider as students juggle their technology and time needs with family and other commitments. As highlighted in the PDF above, you will be scheduling a variety of tasks and activities, and each type has its pros and cons.

Time on task

Emphasize time on task over “contact hours”. Design opportunities to engage deeply with learning in authentic contexts, rather than superficial approaches. Here is a useful calculator for estimating course time. The University of Windsor’s Office of Open Learning recommends that students should spend 6 – 9 hours per week on learning activities in a course, including lectures, watching videos, readings, working on assignments, independent research etc. You may want to read their Fundamentals of Effective Online Teaching Practice for other useful information.

Real Time (Synchronous) versus Anytime (asynchronous)

Ideally, the remote course will have a mixture of real time or synchronous and anytime or asynchronous learning options.

A purely synchronous remote course would involve live streaming lectures without recording them. Such as format is hard on learners, teaching assistants (TAs), and professors for many reasons:

- Technology limits access: students with poor/no wifi struggle to hear, see, and participate. Dropped connections mean missed information. Working in different time zones make attendance difficult.

- Many students will have a poor experience if they can’t connect efficiently. Long, live lectures are difficult to engage in. These issues can lead to poor student experiences and they will understandably complain. These issues could lead to problems of recruitment and retention down the road if courses gain bad reputations.

- A solely synchronous course creates obstacles to learning. Students’ cognitive loads can get too high with too many things to keep track of. You may find it helpful to review Vanderbilt University’s “Effective educational videos” guide. Problems with equity can grow larger. The online format imposes a fixed pace onto students, who may find it too fast or too slow.

Often, explaining basic concepts works well asynchronously (e.g., recorded videos).

Synchronous time (e.g., videoconference) can be used for students to practice in groups and receive immediate feedback. Videoconferences can be very useful in courses, but require high bandwidth and immediacy.

You may want to check out the webinar From Real Time to Anytime Learning by Dr. Michelle Harrison and Marie Bartlett from the Learning Design team at TRU. This webinar addresses how to decide which elements of a course should be in real-time (synchronous) and which can be done anytime (asynchronous), as well as the importance of providing clear instructions, curating resources, course alignment and assessment, and leveraging communication tools.

Considering bandwidth and immediacy

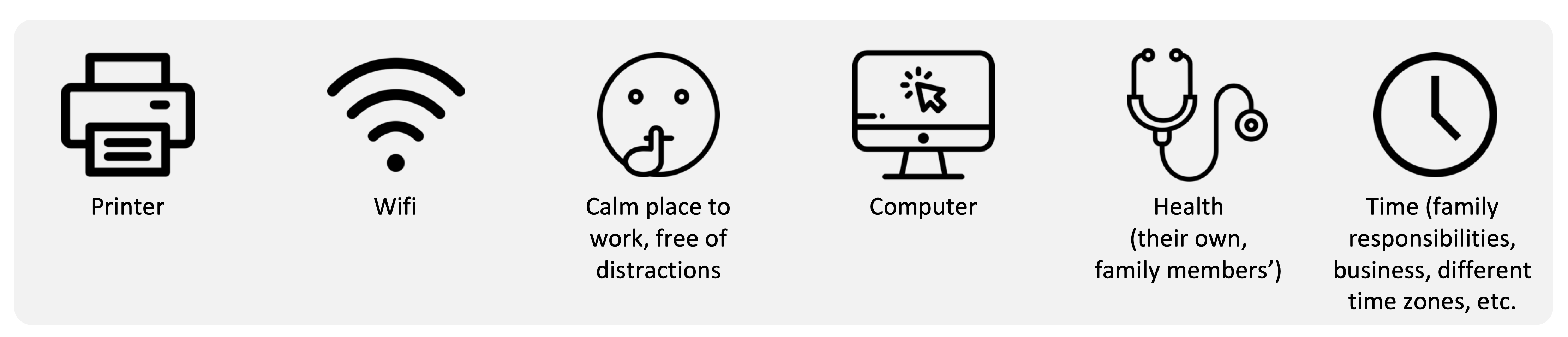

Bandwidth limitations will cause students (or you!) to lose access to the livestream intermittently or for a long time. Bandwidth problems are likely to arise for any number of reasons. Students (or you) will be working from locations that may be subject to wireless interference, remote, or they may not have access to high speed connections. Bandwidth problems can interfere with every part of synchronous teaching, like posing questions for students to discuss in a breakout room (like in BigBlueButton). Students with bandwidth problems may need extra time to download materials before they can use them.

Challenges with immediacy can create or exacerbate equity issues. Immediacy refers to how quickly we expect responses from each other when interacting. For example, when present in person, we anticipate an immediate response when asking someone else a direct question (high immediacy); when we email, a delay is normal (low immediacy).

Immediacy requirements can present challenges. If students must work remotely, they may be working in an environment that is not particularly effective for studying at all times, or one in which there are many distractions or obligations; child care is one example. These issues apply both to students and professors.

We recommend against extensive use of high immediacy/synchronous approaches. Ideally, students will have choices in when to attend to course obligations so that they can also balance their current life obligations.

/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.iddblog.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F03%2Fbandwidth-immediacy-matrix-by-Daniel-Stanford.png)

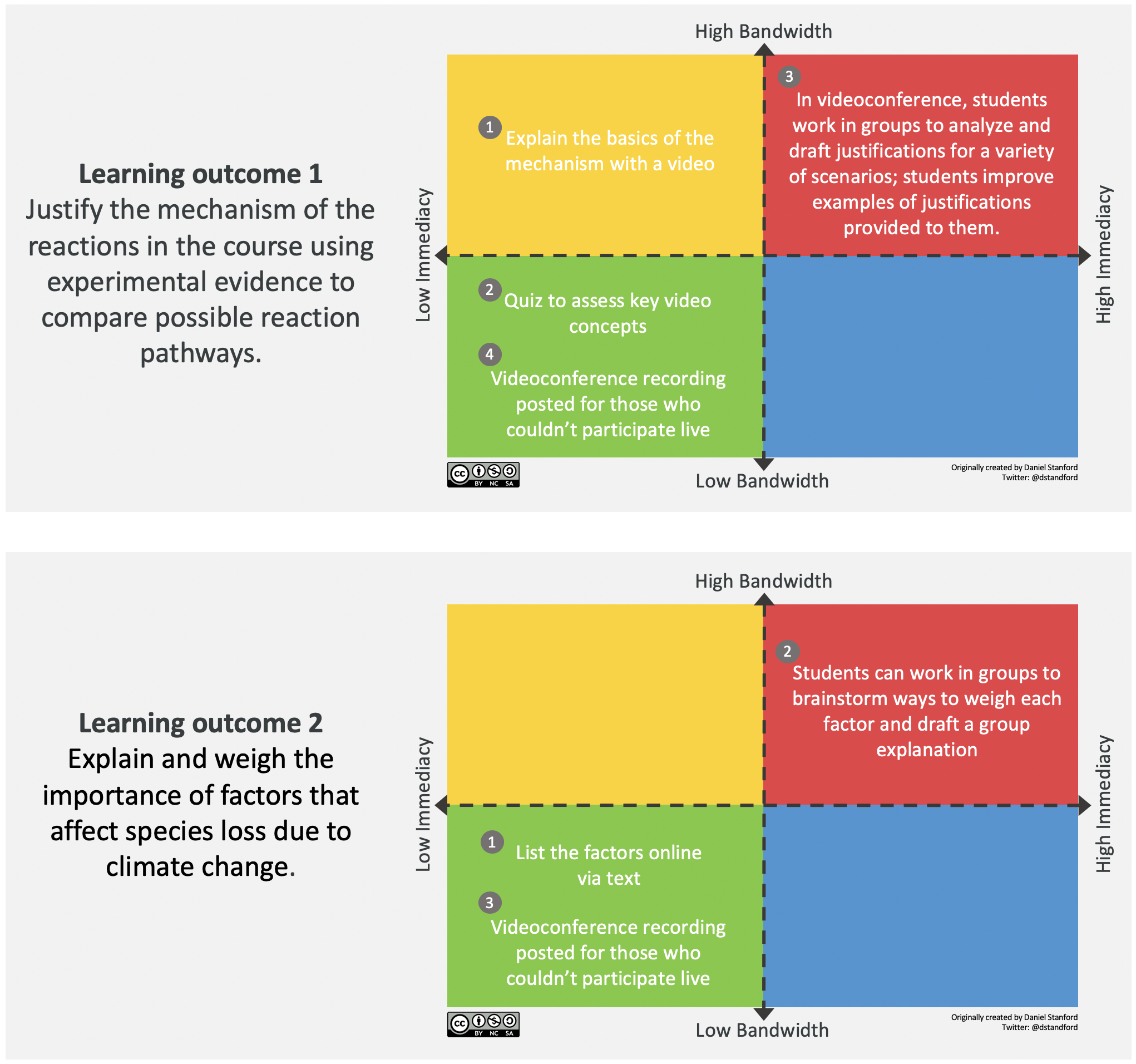

We created a series of examples that suggest ways to find reasonable tradeoffs between immediacy and bandwidth. Our intent here is to take some of the pressure off both students, TAs, and professors.

Examples

Each example that follows is a learning outcome followed by teaching decisions that reflect a specific compromise between high and low immediacy, and between high and low bandwidth requirements.

Developing and establishing community

Building a safe and welcoming space for your learners and developing relationships that will help support an active learning environment takes effort and intention. Building this community in an online space may take different approaches in an online environment. The following resources will help give you some ideas, but building and then maintaining a community of learners will take some careful planning. There is an entire chapter on community building later in this book, but here is a short introduction and links to resources.

Building community online

This resource from KPU “Building Online Commuinty” provides useful tips on questions and respectful communication in online spaces.

Melissa Jakubec, Carol Sparkes, and Michelle Harrison delivered the following webinar that provides some strategies for activities and approaches for setting a welcoming tone and making connections in “That Crucial First Week”.

Maintaining Connections

There are a variety of models for facilitation in online learning environments and promising practices for both synchronous and asynchronous modalities. From a design perspective thinking about everyone’s roles and clearly communicating (and negotiating) expectations for presence and levels of contribution is really important. Maintaining momentum and connection means ensuring respectful and open communication, and as will be discussed further in the learning activities section, there are a myriad of ways to organize the ways that everyone can interact and engage with different kinds of content within the course space.

One well-documented model is the Community of Inquiry Framework, as it highlights the interplay between the different ways everyone can interact within a course. It was designed to allow for deep engagement and interaction between students, instructors and knowledge.

The following chapter “Step eight: communicate, communicate, communicate” in Tony Bates’ book “Teaching in a Digital Age” highlights ways to develop instructor presence, manage online discussions and set expectations.

Aligning Assessments and Activities

Though this is an essential part of the design process, designing activities and aligning these with assessments are chapters within themselves. One word you often hear from instructional designers is “scaffolding”, and here we are trying to describe a process to help students take their past experience and knowledge to continue to create meaningful connections to build their conceptual understanding and frameworks. Based on designing opportunities for learners to engage and interact it is hoped that they can build new knowledge and skills by the end of a learning experience. Ensuring that the activities included in a course build toward a final assessment is an important design strategy which is often termed “backwards design”.

If you would like further reading here is a chapter by Wiggins and McTighe called “Understanding by Design”.

Further Resources

The University of Ottawa’s Teaching and Learning Support Service has created tools to design a blended course that works well for a remote course, too, including how to further analyze the learning environment.

Up Next

The next chapter will focus on choosing and designing learning activities, as well as online learning strategies.

Course alignment refers to the connection between intended learning outcomes, learning activities, assessment, and the course environment.

During synchronous instruction, the professor and students are online at the same time. Synchronous modes can include videoconferencing, discussion boards, etc.

Participants access and work on course materials at different times. Examples include email, discussion forums/chats, and assignments.

Teaching assistants

Temporary storage and processing of information occurs in working memory, which has very limited capacity.

Bandwidth describes the maximum data transfer rate of a network or Internet connection. More info: https://techterms.com/definition/bandwidth

Immediacy refers to how quickly we expect responses from each other when interacting (e.g., professor expects an answer from a student or student expects an answer from a professor). For example, when present in person, we anticipate an immediate response when asking someone else a direct question (high immediacy). In online (and pandemic!) environments, immediate responses can be more difficult when many learners may be taking care of family members, in a different time zone, etc. We can use low immediacy methods to take off some of that pressure, such as email or discussion forums and occasional high immediacy methods such as videoconferencing.