Welcome!

Weyt-kp xwexweytep! We want to first acknowledge the Secwepemc Nation, upon whose traditional and unceded land Thompson Rivers University is located (ne Secwepemcúl’ecw). We are grateful for the Secwepemc Nation’s generosity and hospitality while we live, learn and work in their territory.

Thompson Rivers University humbly acknowledges the location of its campuses in the traditional and unceded territories of Indigenous peoples of the Secwépemc Nation. The Tk’emlúps territory is host to the TRU Kamloops campus; the T’exelcemc is host to the TRU Williams Lake Campus; Tsq’escenemc hosts the 100 Mile House regional centre; the Ashcroft First Nation of the Nlaka’pmx Nation hosts the Ashcroft regional centre; the Simpcw territory hosts the Barriere and Clearwater regional; and the St’át’imc Nation which includes Nxwisten, Ts’kw’aylacw, Sekw’el’was, Líl’wat, Tsal’álh, T’it’q’et, Xáxl’ip, N’quatqua, Xa’xtsa, Skatin and Samahquam hosts the Lillooet regional centre. Thompson Rivers University recognizes the need for research, teaching and service responsive to all Indigenous communities, including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis learners.

This resource has been Adapted from Alison Flynn and Jeremy Kerr’s Remote teaching: a practical guide with tools, tips, and techniques and is designed to help you convert your face-to-face class to a remote course as simply as possible. We walk you through the process, at each step giving a suggestion for a specific tool/technology—the TRU-supported one and our preferred tool if it is different. We also give an example and sources of additional information. We also created a syllabus, course planning documents and other resources that you can modify to suit your own course, if desired. These resources are available in the section called Quick start overview and resource documents.

We have all shared the experience of an emergency translation of in-person teaching to remote teaching in spring, 2020. Each of us improvised a distinct set of tools and approaches that worked in the short term and enabled courses to be concluded in a reasonable way.

The purpose of this guide is to support efforts to plan courses to be offered using remote instruction, identifying a set of tools with supporting examples that can be customized for courses. We also recognize that this emergency involves profound changes to every part of the university experience. Many of us must work under challenging circumstances at home to deliver something that we may have never seen before, let alone created. To be blunt, this transition is stressful.

This guide is intended to take some of the sting out of the process of having to work under such strange and challenging conditions.

We value feedback. In adapting this book from the University of Ottawa, we dove into materials, tools, techniques, and research around best practices for teaching and tried to tailor it to the TRU experience. We have missed things that would make this guide more accessible to colleagues and the process of planning remote teaching less stressful. To this end, please contact us with questions, suggestions, and concerns.

Simple and familiar are ideal

We recommend keeping things simple and using tools and methods that you are already familiar with, to the extent possible. There are so many options that if the ones provided don’t seem like a good fit, please feel free to make changes or reach out (see the Chapter on “Where to find help and advice“).

The fact is that many of us have not seen examples of a “good” remote learning course. In a non-exclusive way, we will provide a number of examples of potentially successful courses and describe the strategy, approaches, and tools that were used to create those examples of success.

Consider how the pandemic may be affecting students

When designing a course for remote instruction, flexibility is important. In this pandemic situation, students have not CHOSEN to take a remote course. They are being required to take courses remotely and many have not even have encountered remote learning or an online course before.

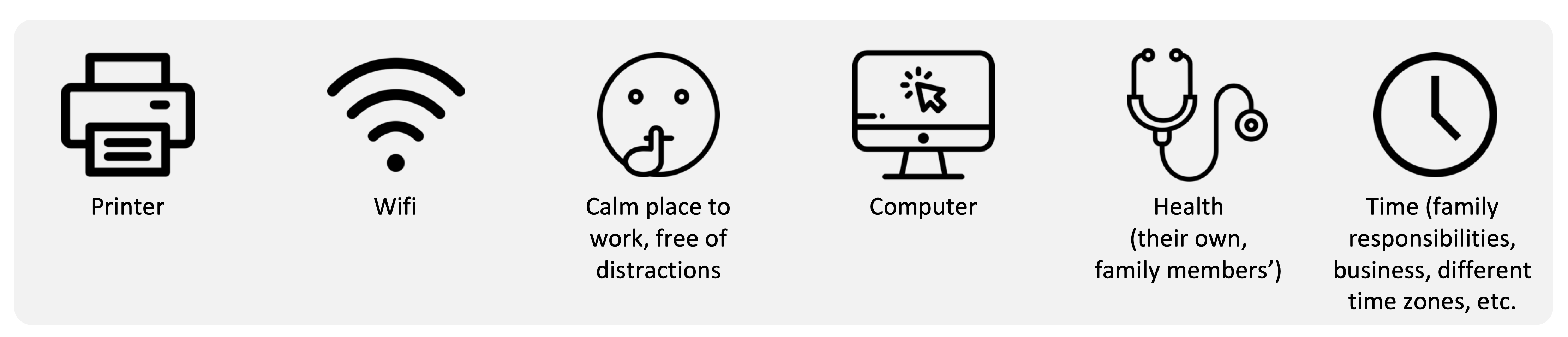

Accessibility matters. Students may have limited access to essential materials for an online course or even to an environment that is suitable for concentration and learning. For example, students may: (i) have no printer, (ii) have poor or no wifi, (iii) not have a calm place to work, (iv) not have a suitable device.

It is vital to remember that we will be working through a global pandemic. Students, their family members, and/or their friends may experience risky health challenges related to COVID-19 as well as those that otherwise arise. Because of pandemic-related travel limitations, some students will be working in a different time zone. In addition to challenges that such time zone differences create that relate to delivery of live (synchronous) content, students also have other obligations associated with their presence in those remote locations (e.g. caring for family members or helping with a family business).

A little about remote instruction

This fall transition is an example of remote teaching and not (for most of us) a formal online course. There’s a full explanation of the differences here. Essentially, a remote course is a normally face-to-face course that is given a distance during time of an emergency (in this instance, the COVID-19 pandemic) to ensure teaching continuity. A remotely taught course is a digital translation of a course that was originally intended to be given in person.

During this pandemic period, neither students nor instructors have any choice about using remote learning/teaching approaches. Considerations and flexibility should be given to the fact that neither is optimally equipped for remote learning/teaching. In contrast, online courses are designed for their medium,. Their design usually involves the support of a team of online education experts, including instructional designers, graphic designers, and a production team. In a way, the distinction between remote teaching and a truly online course is one of degree, but the way content is delivered between the two approaches and indeed the content itself can vary significantly.

Up next

Through each of the chapters that follow, we walk you through the steps of converting to a remote course. Many course variations are possible and we encourage you to adapt these suggestions to best support the students in your course. Please feel free to contact us with suggestions, concerns, or questions by emailing LearningDesign.

A normally face-to-face course that is given a distance during time of an emergency (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic) to ensure teaching continuity. Typically given through online/digital methods. Neither students nor instructors are making the choice to give the course in this way and so considerations and flexibility should be given to the fact that neither is optimally equipped to do so.

A course carefully designed by a team of experts (e.g., course professor, instructional designer, graphic designer) that takes time (months to years!), money, and resources to design and develop effectively. Professors and students CHOOSE to teach/learn in this format.

During synchronous instruction, the professor and students are online at the same time. Synchronous modes can include videoconferencing, discussion boards, etc.